Ever since they were first discovered in India in the 4th century, diamonds have been the byword for luxury and opulence. Whether it’s the Kooh-i-Noor that forms part of the British Crown Jewels or the Taylor-Burton Diamond, made famous by the eponymous Hollywood couple, you might say that diamonds are an investor’s best friend because they hold a specific appeal that spans centuries. A huge draw to diamonds is their scarcity, and people are willing to pay for quality stones – the global market for diamonds is estimated to be worth more than $100 billion.

The natural process that creates diamonds is one that occurs very slowly. Scientists estimate it to take up to 3 billion years. However, over the last century, advances in technology have changed this. We now have the capability to “grow” diamonds in a laboratory environment. The resulting stones are virtually indistinguishable to the untrained eye. If your clients invest in diamonds, read on to discover how they occur in nature, how they’re grown in laboratories, and the importance of getting them regularly valued for insurance purposes.

Diamonds from the rough

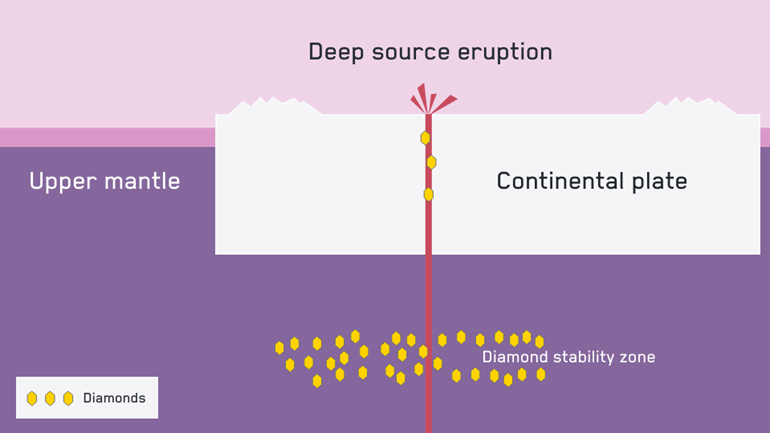

The natural process that creates the vast majority of diamonds occurs deep underground, in the Earth’s mantle. Miles below the surface of the Earth, there is carbon that was either trapped at the time of the Earth’s formation or through subduction – i.e. where the edge of one lithospheric plate is forced below the edge of another.

Contrary to popular belief, carbon in the form of coal or other sedimentary rocks doesn’t form diamonds, as they’re typically comprised of plant debris and are found at 2 miles below the Earth’s surface. 90 miles deeper down, the critical temperature-pressure environment for diamond formation can be found. These conditions are only thought to be present primarily in the Earth’s mantle beneath the stable interiors of continental plates. This is why there are only a few places around the world where diamonds can be found naturally.

The diamonds themselves begin life in the form of carbon-bearing fluids. These fluids travel in the Earth’s mantle, flowing through cracks in rocks. When the fluids percolate, a combination of pressure, temperature, or composition causes the carbon to crystallise from the fluid, creating a solid diamond. The diamonds are brought to the surface by Kimberlite eruptions which bring them up from the mantle at a speed of up to 250 kilometres per hour.

The laboratory methods of growing diamonds

2024 marks the 70th anniversary of the creation of the world’s first lab-grown diamond by General Electric. In the intervening years, two primary laboratory methods have been developed to grow diamonds – High Pressure High Temperature (HPHT) and Chemical Vapour Deposition (CVD).

High pressure high temperature

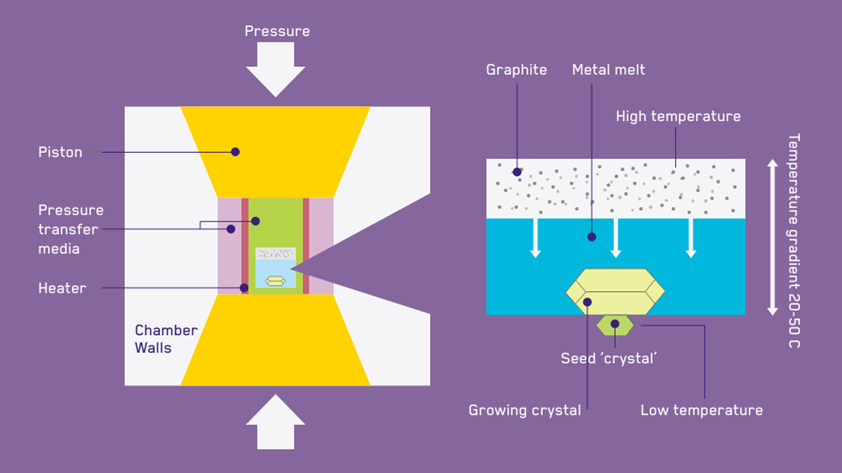

The high pressure high temperature (HPHT) process is designed to replicate the extreme temperatures and pressures found deep below the Earth’s surface. The first thing required in the HPHT process is a small seed ‘crystal’, that is placed into pure carbon.

The seed ‘crystal’ and the carbon are then both subjected to intense pressure and heat inside a specialised chamber. The aim is to create the right conditions to melt the carbon around the seed. A delicate cooling process is then carefully deployed, allowing the carbon to crystallise, forming a diamond that is ready for cutting, polishing, and eventually selling. There are three different manufacturing processes that can be used to make HPHT diamonds – the belt press, the cubic press, and the split-sphere press methods. The belt press method was applied by GE to create the first-ever lab-grown diamond, but all three can work in a similar way to replicate the specific environment required.

Chemical vapour deposition

Chemical Vapour Deposition (CVD) is a newer process, and while it takes longer than HPHT, it is thought to produce higher-quality diamonds. The CVD method starts by taking a seed ‘crystal’, similar to those used in HPHT. This is then placed into a specialised chamber that is heated to around 800 degrees Celsius. When the chamber is up to temperature, it is flooded with a carbon rich gas. Under these conditions, the gas is then ionised into plasma. This can be done with either microwaves or lasers.

The process of ionisation allows the carbon-rich gas to break down. When this happens, the carbon starts to merge with the seed ‘crystal’. A pure diamond is slowly formed, layer by layer as the gas breaks down. What you’re left with at the end is a diamond of a higher quality and clarity than what you would get from the HPHT process. It also requires less energy to do, making it more cost-effective.

Lab-Grown Diamonds in 5 Steps

How to tell the difference between lab-grown and natural diamonds

In the first instance, an untrained human eye can’t tell the difference between a lab-grown diamond and a natural one. They are chemically identical and formed in a scientifically comparable process. Experts can tell the difference through the use of both long-wave and short-wave ultraviolet light (LWUV and SWUV).

Lab-grown diamonds fluoresce differently to natural diamonds under ultraviolet light. Natural diamonds exhibit stronger fluorescence levels when they’re placed under LWUV light when compared to lab-grown diamonds. Consequently, lab-grown diamonds fluoresce more intensely than their natural counterparts when exposed to SWUV light.

In all instances where your clients are dealing with diamonds, they should make sure they get an independent expert involved to verify and ensure that they are buying what has been described in the first instance.

Diamonds are forever, but an insurance valuation isn’t

While there is clearly a lot of work that goes into creating lab grown diamonds, the resulting gems aren’t as expensive as naturally occurring ones. Typically, a lab diamond will cost between 60% and 85% less than a natural diamond with identical carat weight and grades. One of our valuation partners, Doerr Dallas, has plenty of experience in understanding how both natural and lab-grown diamond values fluctuate over time.

Doerr Dallas examined diamonds of a similar weight and clarity, comparing how lab-grown diamonds change in comparison to natural ones over a two-year period. They observed the following changes:

Doerr Dallas have concluded that due to their manufactured origin, the value of lab-grown diamonds has decreased while natural diamonds are keeping their value. In their experience, there isn’t much resale value to

be gained from a lab-grown diamond. Many auction houses will not take them and many of the large fine jewellery houses won’t sell them as they continue to pursue the esteemed rarity of naturally-formed stones.

Even with the difference in price, it is vital to have an accurate valuation in place for insurance purposes.

Rachel Doerr, the MD of Doerr Dallas has a lot of experience in dealing with these types of investments and explains the need for accuracy in valuations over time:

“It is so important to keep your Jewellery valuations up to date as values change in all areas, from the gold price, to diamond values, to coloured stone prices, to manufacturing. Anyone who has not had their jewellery valued or updated in the last two years needs to, otherwise they could get a shock in the event of a loss. If you have never had a valuation, DOEER Valuations would strongly recommend everyone gets all their jewellery appraised and not just items over £10k or £20k.”

Do you need assistance in protecting your client’s assets?

Working with clients who have valuable assets requires accurate valuation data to help calculate replacement costs. Your clients might have a variety of collections that go beyond diamonds, such as collectable sneakers, high-value handbags or luxury watches.

No matter what they have, regular and accurate valuations are critical. If you want to find out more about how our support and expert advice can give your clients peace of mind, get in touch with our Private Client Team.